If you’ve used Linux before and/or have coded using a language such as C, you will have come across a compiler. Though because they’re so easy to use, you might not have actually understood what it is they do.

In a nutshell, compilers simply (I say simply because what they do is actually very complex under the hood) check for syntax correctness, convert source code from “high level” languages to a low level (native) language which your CPU understands and perform optimisation among other things. Due to the conversion and optimisation of code, compiled applications run much faster than when other methods are used. The result of a compilation is a standalone executable application (e.g an .exe file in Windows) which does not depend on any other application in order to run.

I highlighted the words “your CPU” in the previous paragraph because not all CPUs are created equally, and I’m not just talking about the number of cores or their speed either. As this Wikibooks page states:

Compilers are computer programs that translate a high-level programming language to a low-level programming language. The product of a compiler is an executable file, which is made of instructions encoded in a specific machine code. Hence, an executable program is specific to a type of computer architecture.

Further to this point, as this StackExchange answer explains:

At some point, if you’re producing native code, you’ll need to know the details of the chip you’re targeting. You need to be aware of their “quirks” (memory coherency properties for instance) and complete instruction sets to produce an instruction stream that is both correct and reasonably efficient.

Even if you restrict yourself to one instruction set (say x86_64), different brands of chips have different extensions that need to be considered. Different models of the same brand also have instruction set differences (new features added, sometimes old features removed).

What this means is that you can write your applications in a high level language such as C and the compiler(s) will ensure the code work on the users’ machines. As a result of this, even if you and I compile the same source code using the same compiler (assuming the compiler caters for both of our CPU architectures), the executable code will be different.

To really hammer the point home, as this StackOverflow answer says:

You might have a C compiler that generates SPARC binaries, and a C compiler that generates VAX binaries. They both accept the same input language (as defined in the C standard), but produce different programs from it.

Cross Compiling

Say you’ve written an application in C and I want to use it, but my processor’s architecture is different to yours. Further to this, let’s say I have no idea how to compile your code. What can you do in this situation? The answer is use a cross compiler as explained by this StackOverflow answer:

The target architecture is indeed coded into the specific compiler instance you’re using. This is important also for a process called “cross-compiling” - The process of compiling on a certain system an executable that would operate on another system/architecture.

Consider working on an embedded system-on-chip that uses a completely different instruction set than your own - You’re working on an x86/64 Linux system, but need to compile a mobile app running on an ARM micro-processor, or some other type of assembly architecture. It would be unreasonable to compile your code on the target system, which might be so limited in CPU and memory that it can’t feasibly run a compiler - and so you can use a GCC (or any other compiler) port for that target architecture on your favorite system.

Going Deep

If you’re interested in diving deeper, the Wikibooks page I linked to above goes on to say this:

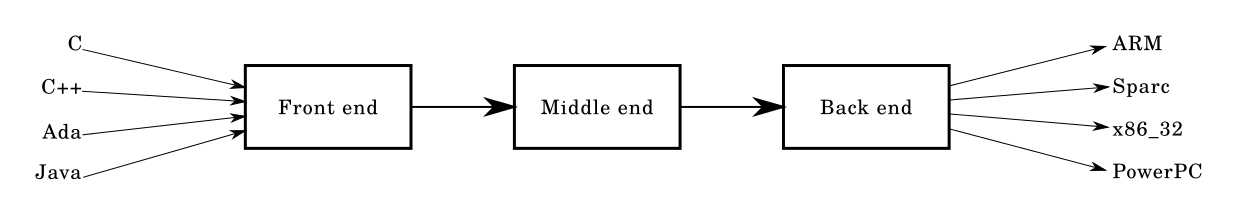

A compiler has a front end, which is the module in charge of transforming a program, written in a high-level source language into an intermediate representation that the compiler will process in the next phases. It is in the front end that we have the parsing of the input program, as we have seen in the last two chapters. Some compilers, such as gcc can parse several different input languages. In this case, the compiler has a different front end for each language that it can handle. A compiler also has a back end, which does code generation. If the compiler can target many different computer architectures, then it will have a different back-end for each of them. Finally, compilers generally do some code optimization. In other words, they try to improve the program, given a particular criterion of efficiency, such as speed, space or energy consumption. In general the optimizer is not allowed to change the semantics of the input program.

The main advantage of execution via compilation is speed. Because the source program is translated directly to machine code, this program will most likely be faster than if it were interpreted. Nevertheless, as we will see in the next section, it is still possible, although unlikely, that an interpreted program run faster than its machine code equivalent. The main disadvantage of execution by compilation is portability. A compiled program targets a specific computer architecture, and will not be able to run in a different hardware.

Diagrams

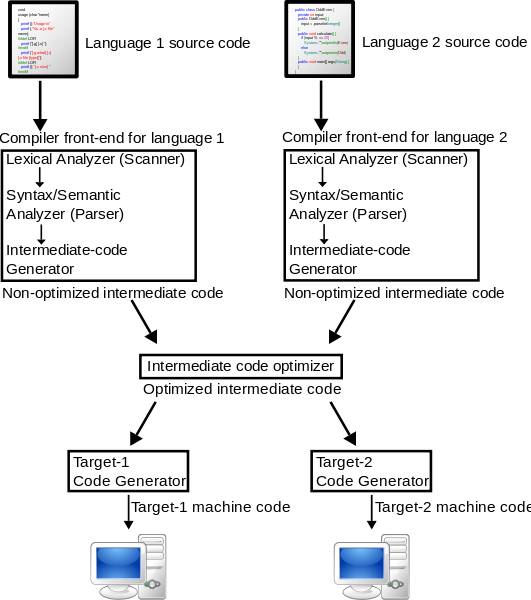

The below diagrams were taken from this Wikipedia article.

The above diagram demonstrates how multiple languages can be fed into an compiler which in turn spits out code which is optimised for the users’ CPU architecture.

The above diagram demonstrates how an application get converted from source code to optimised machine code.

Advantages

As per this techwalla article, some of the advantages of compiled code are:

- Self-Contained and Efficient: Programs that are compiled is that they are self-contained units that are ready to be executed. Because they are already compiled into machine language binaries, there is no second application or package that the user has to keep up-to-date. If a program is compiled for Windows on an x86 architecture, the end user needs only a Windows operating system running on an x86 architecture.

- Precompilation: A precompiled package can run faster than an interpreter compiling source code in real time.

- Hardware Optimization: While being locked into a specific hardware package has its downsides, compiling a program can also increase its performance. Users can send specific options to compilers regarding the details of the hardware the program will be running on. This allows the compiler to create machine language code that makes the most efficient use of the specified hardware, as opposed to more generic code. This also allows advanced users to optimize a program’s performance on their computers.

Disadvantages

The techwalla article I linked to above also states some of the disadvantages of compiled code:

- Hardware Specific: Because a compiler translates source code into a specific machine language, programs have to be specifically compiled for OS X, Windows or Linux, as well as specifically for 32-bit or 64-bit architectures.

- Compile Times: One of the drawbacks of having a compiler is that it must actually compile source code. While the small programs that many novice programmers code take trivial amounts of time to compile, larger application suites can take significant amounts of time to compile. When programmers have nothing to do but wait for the compiler to finish, this time can add up—especially during the development stage, when the code has to be compiled in order to test functionality and troubleshoot glitches.

Ahead-of-time Compilation

Before I wrap this post up I just wanted to point out that the compilation I’ve covered in this post is known as “Ahead-of-time” (AOT). This is because the code is compiled before the user needs to use it. In future posts I will cover alternatives to AOT compilation, such as JIT Compilers.

As always, if you have any questions or have a topic that you would like me to discuss, please feel free to post a comment at the bottom of this blog entry, e-mail at will@oznetnerd.com, or drop me a message on Reddit (OzNetNerd).

Note: The opinions expressed in this blog are my own and not those of my employer.

Leave a comment