In the previous post, What is it?, we gained an understanding of Kubernetes and container orchestrations in general. In this post we’ll cover the three ways in which Kubernetes can be configured.

Kubernetes’ configuration is simply a bunch of Kubernetes objects. Let’s take a quick look at what these objects are, and what they’re used for. The following quotes are from the Kubernetes object documentation:

Kubernetes Objects are persistent entities in the Kubernetes system. Kubernetes uses these entities to represent the state of your cluster. Specifically, they can describe:

- What containerized applications are running (and on which nodes)

- The resources available to those applications

- The policies around how those applications behave, such as restart policies, upgrades, and fault-tolerance

Don’t worry if the above doesn’t make much sense to you, we’ll delve deeper into these concepts later on in this series.

A Kubernetes object is a “record of intent”–once you create the object, the Kubernetes system will constantly work to ensure that object exists. By creating an object, you’re effectively telling the Kubernetes system what you want your cluster’s workload to look like; this is your cluster’s desired state.

The above quote is one of the most important things you’ll need to know about Kubernetes. We’ll dig into this a little later on in this post, but it’s important to keep it at the front of your mind.

OK, so now that we we’ve got objects out of the way, let’s look at how to administer them.

Configuration Methods

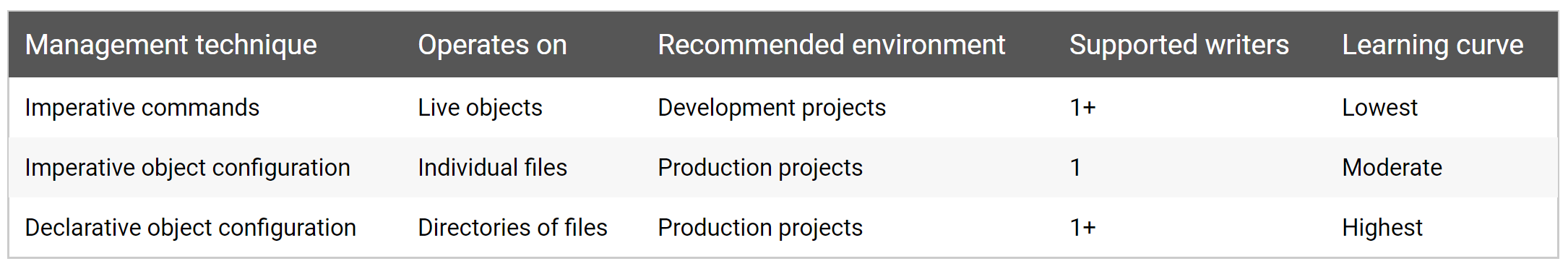

There are three ways Kubernetes objects can be configured. A high level comparison can be found here, with more detailed information found here:

And this post from Sebastian Goasguen contains some great information too.

Note: It is important to remember that you should use only one technique to administer a cluster. Not following this advice can result in undesirable outcomes.

Imperative Vs Declarative

As per the list above, we’ve got one declarative and two imperative configuration options. If you’ve used configuration management tools like Ansible, Puppet and Chef, you’ve likely come across these terms before. For those who haven’t, please read on.

Imperative methods can be thought of as step by step guides. For example, “spin up 3 instances of Ubuntu, pull the latest git commit, install nginx on each instances”, and so on. The problem with imperative methods is that they’re not idempotent. This means that if we re-ran the above configuration, we’d end up with 6 instances. If we then changed the commit hash and re-ran the configuration again, we’d have 9 instances.

Note: Idempotency refers to things which return the same result every time they are called. In the above example, the number of instances increased each time the configuration was run. Therefore, it is not idempotent.

With declarative methods, we simply tell the system what we’d like the end state to look like, and the system makes it happen. Let’s run through the above example again, but this time using a declarative approach.

Running the configuration the first time would result in 3 instances being spun up. If we ran it a second second time, it would result in no changes being made. This is because declarative methods are idempotent. We said we wanted 3 instances and 3 already exist. Therefore, there’s nothing more for the system to do. This gives us complete control and visibility of what is being deployed.

Finally, if we then changed the commit hash and ran the configuration again, we’d see 3 new instances being spun up, and the original 3 being terminated. This is because our desired state configuration has changed from 3 instances with the original hash to 3 instances with the new hash. As the original instances are no longer in our configuration, the system will automatically clean them up for us.

To summarise:

- Imperative

- Provides less control

- Requires manual clean up

- Declarative

- Automatic clean up

- Define what you’d like the end state to look like and let the system figure out how to achieve it

Which method should I use?

The Kubernetes documentation provides the following comparison for the three methods:

Though the declarative method has the highest learning curve, it is the only option that is recommended for production use and can be used by multiple writers. It is for this reason that it should be the method of choice.

Even though the docs say that it’s OK to use the imperative commands and configuration in some cases, my advice is to use the declarative method for all cases. The reason being that:

- Configuring your dev and prod environments in a consistent manner eases administration

- Always plan ahead - though there may be only one admin today, additional admins may come on board at a later date

Other things to keep in mind are:

- Imperative commands do not support the full Kubernetes feature set

- Imperative configuration can result in undesirable outcomes, as per the following quote:

Warning: The imperative

replacecommand replaces the existing spec with the newly provided one, dropping all changes to the object missing from the configuration file. This approach should not be used with resource types whose specs are updated independently of the configuration file. Services of typeLoadBalancer, for example, have theirexternalIPsfield updated independently from the configuration by the cluster.

If you’re already using an imperative methods but would like to migrate to declarative, have a read of the Changing management methods section of the Kubernetes documentation.

Infrastructure as Code

There’s one last point I’d like to make before wrapping this post up. The declarative method is known as “Infrastructure as Code” (IaC). If you’ve used tools like Terraform and/or CloudFormation, you’ll already be familiar with this term. For those who aren’t, Wikipedia gives a great definition of it:

Infrastructure as code (IaC) is the process of managing and provisioning computer data centers through machine-readable definition files, rather than physical hardware configuration or interactive configuration tools.

The IT infrastructure meant by this comprises both physical equipment such as bare-metal servers as well as virtual machines and associated configuration resources.

The definitions may be in a version control system. It can use either scripts or declarative definitions, rather than manual processes, but the term is more often used to promote declarative approaches.

Because IaC is often used with a version control system (VCS) such as git, we gain all of the benefits the VCS has to offer:

- Code review:

- Built in diff’ing tool(s)

- Only peer reviewed changes are permitted

- Integration with CI/CD:

- Linting

- Pipelines:

- Test in dev before rolling out to prod

- Automated deployment & recovery

- Auditing:

- What changed, when it changed and who changed it

If you’re not using IaC already, I highly recommend you start now. It is a fantastic methodology. Once you get started you’ll wonder how you ever lived without it!

As always, if you have any questions or have a topic that you would like me to discuss, please feel free to post a comment at the bottom of this blog entry, e-mail at will@oznetnerd.com, or drop me a message on Reddit (OzNetNerd).

Note: The opinions expressed in this blog are my own and not those of my employer.

Leave a comment